Asian American Audience Members’ Reactions to Crazy Rich Asians

The 2018 film Crazy Rich Asians was a critical and commercial success. The romantic comedy follows the story of Rachel Chu, an Asian American economics professor, who travels to Singapore for a wedding and meets her boyfriend Nick Young’s ultra-wealthy family. The family matriarch initially disapproves of the pairing, but Chu wins her over. The film received widespread acclaim for its representation of Asian American characters. In a recent article published in NCA’s Critical Studies in Media Communication, Lori Kido Lopez examines online discourse related to Crazy Rich Asians and its impact on Asian American viewers.

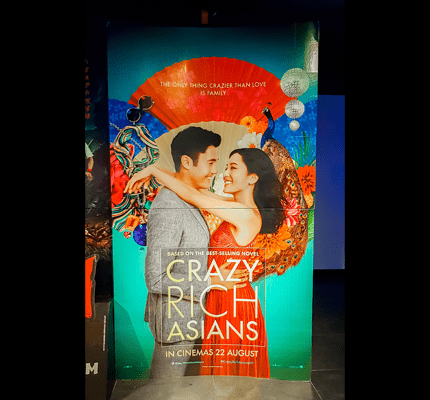

Marketing Crazy Rich Asians

Warner Brothers explicitly marketed Crazy Rich Asians to Asian Americans through multiple avenues, including working with popular Asian American YouTubers and having an early VIP screening called Fashion Night Out that featured high-profile Asian American designers and influencers. Asian American activist groups also bought out hundreds of theatres, so that any Asian American who wanted to see the film could see it. People used the hashtag #GoldOpen to raise awareness of the movement and of the importance of ensuring the film’s success. Lopez compares the enthusiasm for Crazy Rich Asians to the support that Black moviegoers offer for films known as “must-see Blackness.” Crazy Rich Asians attained a sense of “must-see Asianness,” which describes the importance of Asian American support for Asian American cultural products.

Crazy Rich Asians and “Emotional Excess”

Many journalists wrote about the emotional experience of seeing Crazy Rich Asians and the importance of seeing non-stereotypical representations of Asian characters. For example, one reporter wrote: “The most common response I’ve heard to watching Crazy Rich Asians is ‘I cried’: I cried 30 seconds into the film, I cried in the last act, I cried when they played mahjong, I cried during the wedding scene, or I cried on Twitter later that night.” Lopez writes that crying was an expected response to the film because the film was a romantic comedy that contained elements of melodrama.

However, Lopez also argues that these tears represent a larger racialized moviegoing experience. According to Lopez, within American culture, Asian Americans are expected to be happy and optimistic. Asian Americans are often stereotyped as a “model minority” who are not angry, and are diligent, hard-working, and generally “quiet.” Lopez argues that Asian Americans’ teary responses to Crazy Rich Asians challenge these stereotypes by showing emotional excess.

Asian Americans seeing the film may have also felt the weight of expectations of success for the high-profile film. According to Lopez, anxiety related to representation may include “the fear of humiliation or shame if audiences don’t like it or if it is a mocking or degrading portrayal, alongside the desperate hope that it ultimately performs well enough to open doors for future Asian American projects.” For example, journalist Kat Chow expressed how some Asian American viewers may have felt at Crazy Rich Asians screenings, especially screenings dominated by white audiences: “I worried what this [white] audience would make of the movie. Would they get the jokes? If they laughed a ton, would it mean this movie wasn’t meant for me? What would all this suggest about [the film’s] eventual box office take?”

Furthermore, while the term “Asian American” refers to Asian immigrants and their descendants in the United States, Lopez found that other members of the Asian diaspora identified with the Asian American experience. Asian Australian journalist Michelle Law described her experience watching Crazy Rich Asians in The Sydney Morning Herald: “My reaction took me by surprise. I wasn’t expecting to be so affected by seeing a protagonist that looked like me and locations that felt like home. I wasn’t expecting to hear a soundtrack sung in languages from my mother country. I felt seen for the first time in years, well, precisely 25 years, which is when The Joy Luck Club, the last major studio film to feature an all-Asian cast, was made.” Lopez notes that Law does not distinguish between Australian and American media products, but writes about mainstream media products generally. Responses like these demonstrate the connections amongst the Asian diasporic community and show that diasporic Asians are connected by a lack of media representation.

On Twitter, users often include gifs or images to illustrate their feelings or emotions related to a tweet. Lopez examined many tweets in response to Crazy Rich Asians and found that Asian users incorporated a variety of gifs of celebrities crying in their tweets, including tweets featuring Anne Hathaway, Donald Glover, Steven Colbert, and Oprah. The only Asian figures represented through gifs were Sandra Oh in Grey’s Anatomy and members of the Crazy Rich Asians cast. Some people also posted pictures of themselves after seeing the film. Lopez argues that the use of gifs of Black celebrities can be seen as “digital blackface.” However, Lopez also suggests that such use must be considered in light of the lack of representation of Asian Americans in Hollywood. Because there are few complex and prominent roles for Asian Americans, they are absent from gifs, with the exception of Sandra Oh. In addition, Asian users turned to images of their own faces to represent their feelings. According to Lopez, this is particularly important in challenging stereotypes that cast Asian Americans as not very emotionally expressive.

Conclusion

In the article’s conclusion, Lopez notes that the responses described above were only a fraction of the responses to the film. Some viewers criticized the film for a number of reasons, including perpetuating the “model minority” myth and minimizing the presence of dark-skinned Southeast Asians in Singapore. Lopez writes that there is not, and cannot be, a unified response to the film—not all viewers loved it or felt represented by it. Lopez concludes that discussing the plurality of responses to the film and looking at social media posts and news articles is necessary going forward to understand how Asian American audience members respond to Asian American media products.