Roberto Gabetti and Aimaro Isola’s housing complex in Ivrea in northern Italy fulfilled Adriano Olivetti’s vision for a more human industrial city, but 50 years later, little remains of this utopian experiment

By the time Adriano Olivetti died at the age of 59 in 1960, the famous typewriter company founded by his father Camillo more than 50 years earlier, employed over 36,000 people. In the town of Ivrea, Olivetti employees and their children had access to top-quality services, including canteens, healthcare, schools, film festivals, exhibitions, concerts, courses, conferences and a library with around 90,000 volumes.

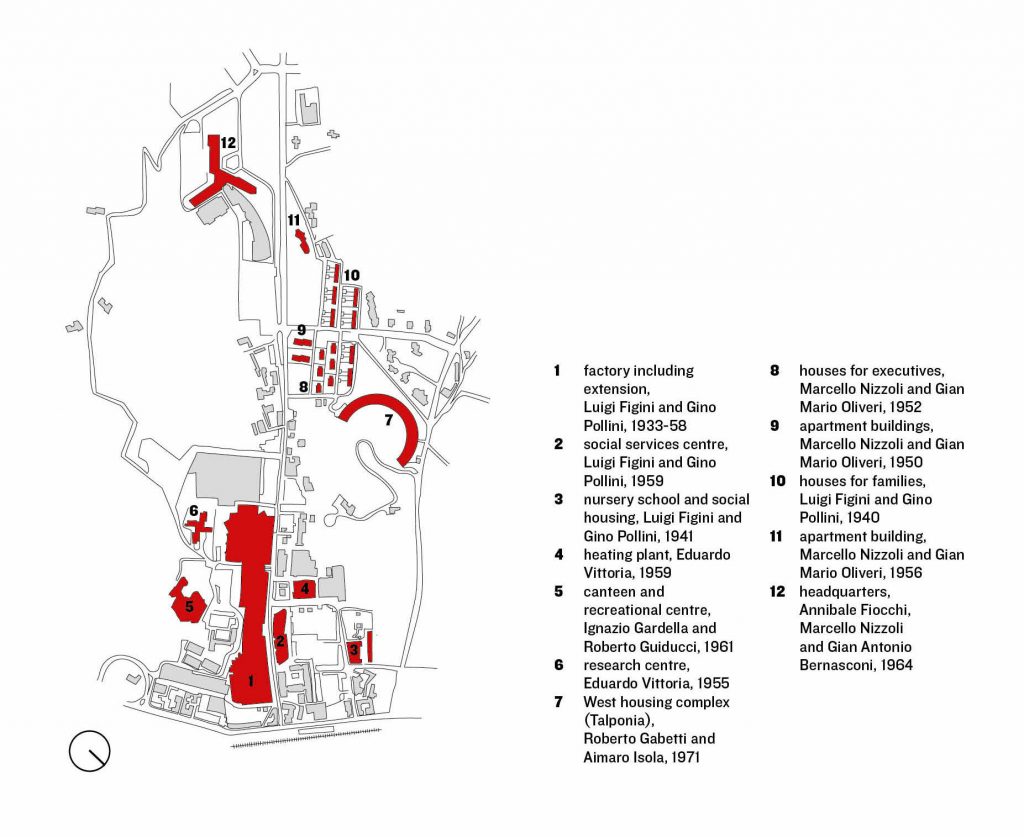

Building the first factory a few kilometres from the centre of Ivrea in 1908, Camillo aimed to escape the Taylorist dynamics he saw in the US. With a similar sentiment, Adriano believed that workers should not be uprooted, and that by staying and working where they lived, workers could contribute to their community. Contrary to the big companies such as Fiat and Pirelli that made nearby Turin and Milan attractive, Olivetti focused on rooting a community around the territory of Ivrea and growing cohesion, creativity and quality from within. Adriano was interested in the new generation of Rationalist architects from Milan, and approached the young Luigi Figini and Gino Pollini for a series of projects to add to Ivrea’s industrial area, including extending the factory and building new workers’ facilities. Initiated in the 1930s, the work was completed in several phases after the Second World War.

The enfilade of architectural masterpieces flows past the car window, the glass facades of Figini and Pollini’s factory unravelling like a ribbon that could continue forever, a sort of Bauhaus unrolled along the street. Adriano Olivetti’s citadel, which became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2018, is grafted on to the main axis that was Ivrea’s first paved road. An old employee recounts that local inhabitants would go and look at the road as if it were a special attraction; the ‘new’ had arrived, a road ‘like in America’.

The West housing complex, designed by Roberto Gabetti and Aimaro Oreglia d’Isola in 1968 and completed in 1971, was part of the last phase of development of the industrial citadel, together with the East housing complex the other side of town, designed by Iginio Cappai and Pietro Mainardis, which opened in 1976. Known affectionately as Talponia (‘mole town’), the building is hidden in the topography, dug into the ground like a mole hole. It reveals itself only after passing through an adventurous sequence of immersions in the landscape, from the industrial plain, to a country hill, into the darkness of a cave and, finally, the arcadia of an unspoilt secret garden.

‘There it is, a passage to another world: behind us, the car; in front of us, a lush grove framed by thin, full-height glazing’

Past Marcello Nizzoli and Gian Mario Oliveri’s villas from 1952, the road circles a large, curved lawn, then suddenly climbs up two tiny hairpin bends to be finally swallowed up by a thin crack in the hillside. The first contact with the building happens there, inside its concrete belly; the road continues in a 300-metre-long arc underground. The tunnel is marked by structural slats arranged radially on the ceiling, with cones of light from skylights above. In front of a parking space, a small yellow door digs into the circular concrete shell. There it is, a passage to another world: behind us, the car; in front of us, a lush grove framed by thin, full-height glazing.

‘Along the 11-metre depth of these units’, the architects wrote in L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, ‘we have tried to represent the route which from the automobile-machine … brings one to see one of the few performances which man may – though rarely – contemplate: mutations of a wood through the changing seasons.’ The efficient switch from the car to the flat spares the tired worker from useless neighbourhood pleasantries, offering instead a corner of peace and an immersion in nature.

Even inside, the transition between spaces is minimised and the deep plans, which take in air and light from only one side, did not feature any internal divisions. A series of PVC sliding curtains divided spaces into rooms if needed, and the whole space was conceived by the architects as an internal facade. Devoted to short stays of trainees, managers and consultants, the flats were furnished with movable objects to fit in with a nomadic lifestyle. Modular furniture could be composed in various ways, maintaining a neutral and functional character, while some special elements, such as Gabetti and Isola’s ‘Tapizoo’ series of large rugs depicting wild animals, were intended to add an expressive and somewhat surreal touch to the flats.

Never abandoned, but heavily compromised and underused following changes in the company’s internal policies in the 1980s, the building was put up for sale by Pirelli Real Estate, which had acquired part of Olivetti’s shares and properties in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Sold at bargain prices, all the flats were soon taken by new owners, many of whom acquired several units at once in order to rent them out. From the moment the building was parcelled out, the original idea of the agile, ‘smart’ lifestyle fell apart.

The single-aspect flats open up to the landscape, immersing the weary worker in the beauty of nature after a day’s work

Credit: Nick Ballon

With the change of ownership, very few dwellings have maintained their original open-plan character, with many adapted to create different functional zones. Some ‘imaginative’ solutions have been found to create more sheltered spaces, such as alcoves and translucent partitions. The original blinds, conceived by the architects as a series of light-grey vertical slats, making the facade appear to bristle and vibrate, began to be replaced by more opaque and variously coloured textiles, according to the new inhabitants’ tastes. Within a few years, the meticulously designed glass wall broke down into fragmented sections, shattering the abstraction of the building’s only elevation. However, in preparation for Ivrea’s UNESCO nomination in 2018, the owners decided to introduce a few simple rules, including a uniformity of curtain colour, to reconstitute the original continuity of the facade.

Articulated by a modulation of aluminium frames, this convex wall of glass changes colour every hour of the day, reflecting the environment. The hillside grove, part of the estate of the Olivetti family’s villa, now used as the local HQ of the Olivetti Foundation, is the theatre towards which this contemporary metal crescent is oriented. Like a theatre stage, it is an object of admiration but not of interaction, being inaccessible to the public and the inhabitants of the complex. Manfredo Tafuri described it as an ‘arcadia severa’ (‘severe arcadia’), in which, precisely due to its inaccessibility, an astonishing biodiversity comes to life, which would be hard to imagine in a complex of 82 flats built in the middle of an industrial citadel. During the day, dozens of bird species can be heard, while at night, wild boars approach almost up to the windows.

The original apartments included flexible modular furniture and uniform vertical blinds

Credit: Nick Ballon

Halfway between an earthwork and a piece of Minimalist art, this project represents a fundamental step in the career of the two architects from Turin. Marking the natural landscape with a geometric sign, the building was in the same vein as a series of experimental projects (such as the Università della Calabria by Gregotti Associati designed in 1974), which set out to intervene directly in the landscape.

Today we might recognise in the approach of concealment in the ground the ‘camouflage’ techniques widely used in more recent design practices, aimed at making entire buildings disappear under carpets of plants, as if to express a sort of reparation towards the environment and the resources that the act of building has taken away. However, this was not Gabetti and Isola’s intention when they presented the project to the clients, a crescent embedded in the ground rather than the ‘iconic’ building they had been asked to build. The architects used the elements of the environment as actual building materials, convinced of their extraordinary, inexhaustible expressive power, capable of continuous regeneration, perfectly immune to obsolescence. The landscape changes but does not age, the building seems to say, and so architecture can take advantage of this spell by acting with it, rather than against it.

Some inhabitants have replaced the original vertical blinds with curtains, though recent rules enforce a consistent neutral colour

Credit: Filippo Romano

Besides being a moment of change in the work of Gabetti and Isola, it was also a period of great change within the Olivetti company. At the same time the East and West housing complexes were built in Ivrea, Kenzo Tange built the Yokohama Technical Centre; James Stirling, the extension of the Haslemere Training School; and Louis Kahn the Harrisburg plant in Pennsylvania, all for Olivetti, bringing the company to a total of approximately 74,000 employees worldwide. The Valentine typewriter, designed by Ettore Sottsass and Perry King in 1969, was perhaps the most iconic of all Olivetti products, and marked the company’s peak, which would soon give way to an economic system dominated by the dematerialisation of markets into networks and services. After Adriano’s death, the company began a path towards its financialisation, marked by the entry of new shareholders such as Fiat, Pirelli and Mediobanca, and the sale of the electronics division to General Electric. This happened immediately after the presentation in New York of the Olivetti Programma 101: the first programmable desktop computer that years later would be recognised as a forerunner of the PC.

Today, only a small part of Olivetti’s production buildings in Ivrea are occupied by activities that are linked to the company. Some of them are occupied by new firms that were born from the re-employment and sale of specific branches, mostly in the sector of mobile phones. Ignazio Gardella and Roberto Guiducci’s canteen, built in 1961, is now used as a call centre, while Figini and Pollini’s main buildings are only partially occupied. But as journalist Marco D’Eramo has written, the inclusion of a small town in the UNESCO list is the kiss of death for its community. These days, walking around the streets of the ‘industrial city of the 20th century’ is a rather depressing experience. Of the East housing complex, built as a hotel (Hotel La Serra) and service centre in the city’s heart, only the cinema and auditorium remain in use. I asked a passer-by if the cinema was still open but he couldn’t remember.

The housing complex was designed down to the last detail, including distinctive light fittings

Credit: Nick Ballon

The Talponia typology, designed for short business stays, lends itself perfectly to today’s short sojourns of scholars and tourists who use Talponia to travel to the same places as their predecessors, albeit for different reasons, and this time via Airbnb. Judging by the parked cars and evening lights, barely a third of the 82 flats appear to be regularly inhabited, and this low density certainly contributes to the quiet and peaceful atmosphere of the complex. A nursery school occupies the first three flats, with a small portion of the garden for private use. There are not many inhabitants here, but a very rich, incredibly active and varied fauna that seems to care neither about the financialisation of the markets, nor the pandemic, nor the patrimonialism of industrial buildings or the urban phenomenon of shrinking cities. The spectacle staged by Gabetti and Isola in this natural theatre has not changed, or rather, it is constantly changing, just like they wished.

Translated by Davide Tommaso Ferrando

Architectural Review Online and print magazine about international design

Architectural Review Online and print magazine about international design